A MEDITATION FOR HOLY SATURDAY

Holy Saturday, the day between Good Friday and Easter Sunday, is one of the most mysterious and profound days in the Christian year. The Bible tells us a great deal about the events of Holy Week—from Jesus’ triumphant entry in Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, to the Last Supper on Thursday, to his crucifixion and burial on Friday, to the resurrection on Sunday—and these events are commemorated in our worship on these days.

But Holy Saturday is a day of silence. Of it, the Gospel author Luke writes simply, “On the sabbath they rested according to the commandment” (23:56). For Jesus’ friends, followers, and family, it was a day of deep grief and overwhelming disappointment. The teacher and miracle-worker they had followed, whom they had come to believe was the prophesied Messiah, the saviour, had died on the cross the previous day. His movement was shattered and his followers were scattered, terrified, and in hiding.

Or so it seemed. The Gospel accounts tell us what was happening in the land of the living on Holy Saturday. But elsewhere in scripture we have references to the work that Jesus was doing, even in the grave.

1 Peter 4 says that “the gospel was proclaimed even to the dead, so that, though they had been judged in the flesh as everyone is judged, they might live in the spirit as God does”.

This rather mysterious reference is contextualized by Ephesians 4, which says of Jesus ‘When he ascended on high he made captivity itself a captive; he gave gifts to his people.’ When it says, ‘He ascended’, what does it mean but that he had also descended into the lower parts of the earth? He who descended is the same one who ascended far above all the heavens, so that he might fill all things”.

And Psalm 139 prophetically proclaims the presence of God even in hell: “Where can I go from your spirit? Or where can I flee from your presence? …if I make my bed in Sheol [the place of the dead], you are there”.

These scriptural accounts help form the basis for the ancient Christian conviction summed up in the Apostles’ Creed—one of our oldest summaries of Christian belief—that after Jesus died, he “descended into hell”, or the realm of the dead.

According to this understanding, Jesus was not simply dead and buried on Saturday. Instead, he carried out the victory of the cross, destroying the power of sin and death by bringing the light of the gospel to all who had died.

In the Eastern Orthodox tradition of iconography, two icons stand out for particular use on Holy Saturday. The first is known as the “Lord of Glory” icon, also called “Extreme Humility”. It shows Jesus dead in the grave, and the title references the culminating lines of Psalm 24, which refers to the conquering “Lord of Glory”. Jesus is the one who triumphs through his death.

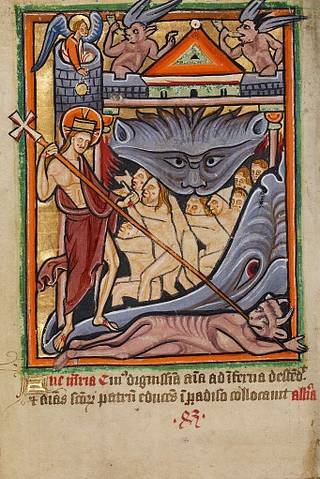

The second is a depiction of the resurrection that includes the “Harrowing of Hell”, which is the ancient name given for Jesus bringing light to the domain of darkness. In this icon, you can see what was spiritually at work in Jesus’ death, as he storms Hell, grasps Adam and Eve by the hand and leads all of the faithful departed out of death.

Taken together, these two icons give us both sides of Holy Saturday: the cold, hard fact of Jesus’ death and burial, and the spiritual triumph of his conquest of death. The Gospel of Nicodemus, a Christian devotional writing dating from the fourth century, offers a remarkable dramatic depiction of this reality, envisioning the scene in Hell on Holy Saturday through a dialogue between Satan and Hell (Death), as they realize with dawning horror what it means that they have brought Jesus into their midst. It’s well worth a read.

Holy Saturday is a pause, a moment of silence between the fury of Good Friday and the jubilation of Easter Sunday. Take time to reflect in prayer, this Saturday, on the sabbath rest of Jesus in the grave, as he harrowed Hell and left it shattered forever.